University of North Carolina Athletics

Extra Points: The Lanier Domino

October 24, 2025 | Football, Featured Writers, Lee Pace, Extra Points

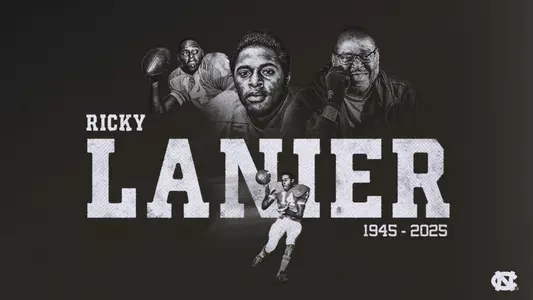

EDITOR'S NOTE—Ricky Lanier, the first Black scholarship football player at Carolina (Letterman 1968-70), passed away Oct. 1 at the age of 76. He will be recognized pre-game in Kenan Stadium Saturday prior to the Carolina vs. Virginia game.

Jim Tatum knew of an outstanding football prospect in Shelby during his time as the Tar Heels' head coach from 1956-58. He alerted his friend Murray Warmath, the coach at the University of Minnesota, and told Warmath to offer Bobby Bell a scholarship. Warmath hemmed and hawed as he hadn't actually seen Bell with his own eyes, and there was no film of Bell available. "Look, if he doesn't work out, I'll pay for his scholarship," Tatum said.

Earle Edwards was similarly impressed with the prospects of a quarterback from Fayetteville named Jimmy Raye. Edwards, the N.C. State coach from 1954-70, called his friend Duffy Daugherty, the head coach at Michigan State, and put in a word for Raye, who was already on the Spartans' watch list because assistant coach Cal Stoll had been impressed with Raye's performance in a high school all-star game in Durham.

Ironically, Raye's first start for the Spartans was the season opener in 1966, when he led Michigan State to a win over the Wolfpack and Edwards.

"Would I have liked to have played at N.C. State or North Carolina, 60 miles from home instead of going 1,600 miles away?" Raye says today. "Of course I would. I would love to have played in my home state. But there weren't any opportunities. That's just the way it was back then."

Indeed, coaches like Tatum and Edwards were relegated to referring top Black prospects to their friends in the Midwest at a time before the color barriers had fallen at Southern institutions.

Bell played at old Cleveland High School in Shelby before integration and was a linebacker on the 1960 Minnesota team that won the national title (and no, Tatum did not have to reimburse Warmath for the scholarship). He also was a two-time first team All-America, in addition to winning the Outland Trophy and being recognized as the UPI Lineman of the Year in 1962. Warmath asked him if he knew any other good Black players from North Carolina. Bell said he had a good friend in Winston-Salem. That's how the Golden Gophers got Carl Eller.

Bell and Eller are both in the Pro Football Hall of Fame via their outstanding careers with the Chiefs and Vikings, respectively.

Gene Sigmon, a Tar Heel Letterman in 1962-63, mused about roster makeup from his era many years later. Sigmon was team captain in 1963, when the Tar Heels posted a 9-2 record, won the ACC title and powdered Air Force 35-0 in the Gator Bowl.

"You put Bobby Bell and Carl Eller on our team in the early sixties, and maybe we're talking about national championship instead of ACC championship," Sigmon said at the team's 50-year anniversary in 2013.

Fortunately, those inequities began changing just a few years later.

Dean Smith signed Charlie Scott as Carolina's first Black scholarship basketball player in 1966. Scott entered Chapel Hill in the fall of '66, played on the junior varsity basketball team and then had a record-setting and All-America career through his senior year in 1970.

Bill Dooley was hired as the Tar Heels' new football coach in December 1966, and one of his early recruiting targets was a dynamic quarterback and athlete from Williamston named Ricky Lanier.

Lanier was a standout on the 1966 E.J. Hayes High School team under Coach Herman Boone (of Remember the Titansfame) and was responsible for 13 touchdowns in one game—eight passing and five running in an 80-0 win over Snow Hill. Dooley wanted Lanier for the Tar Heels and arranged to have Scott and fellow basketball player Larry Brown serve as Lanier's hosts on his recruiting visit in early 1967.

"Larry and Charlie were just honest with me about what to expect," Lanier says. "I didn't think twice about being the first Black football player, but Larry and Charlie just did such a good job."

Lanier joined Dooley's first recruiting class that included a quarterback from North Wilkesboro named John Swofford and a tailback from Long Island named Don McCauley.

"He was a quality guy and on the outside was outgoing and happy-go-lucky," says Swofford, who lettered for three years and went on to a noted career in athletic administration, including 17 years as Carolina's athletic director and 24 as commissioner of the ACC. "You'd have to have walked in his shoes to know for sure, but any problems he had outside of football he seemed to handle very well. He was certainly accepted on our football team as just one of the guys."

McCauley echoes that sentiment.

"In our mind, there was no black/white," he says. "But Ricky was just another football player. It was an attitude of, 'Get to work and go play ball.' He was accepted for his personality and athletic ability."

Lanier displayed that athleticism at both quarterback and receiver while earning letters from 1968-70. He was moved to receiver but came back to quarterback for an early November game in 1969 against VMI because of a rash of injuries at the position. Lanier gained 218 yards running but lost 44 on quarterback sacks and a pitch-out that went awry to net 174 yards rushing for the game. That total remains a school record for rushing yards by a quarterback in a single game.

"Ricky made some outstanding runs," Dooley said. "We moved him to split end and then back to quarterback, and he gives us a good effort wherever we play him."

Swofford and McCauley wonder how Lanier's skills might have translated into modern college football with more passing and emphasis on getting elite athletes in space.

"In today's game with wide-open offenses and the way the ball is thrown so much, I think Ricky could be an extraordinary player—either as a receiver or a quarterback,"

Swofford says. "But that wasn't the kind of offense we ran at that time, very few teams did. Dooley's system was run-oriented with the option and pitch and not much throwing the football. It was a ball-control approach. It paid off ultimately as we won back-to-back ACC championships. Still, you wonder what he could have done today."

"Ricky was the first 'scrambling quarterback,'" McCauley says. "He had a great sense of where the defense was. He could really break down a defense."

After graduating from UNC in 1970, Lanier joined the coaching staff at North Carolina Central and later worked for IBM. He moved to Greensboro in 1990 and taught science at West Guilford High before retiring in 2016.

"I was never called names," Lanier said years later. "I think that the South and the nation just were in a transition when I came to Carolina. I never had any problems. The camaraderie with my teammates was great."

Lanier was the first domino to fall, and the color barrier officially fell for Carolina. One year after Lanier's arrival, linebacker James Webster and defensive end Judge Mattocks joined the squad. By 1974, the Tar Heel roster included six Black players out of 83—Charles Waddell as a senior co-captain along with senior defensive tackle Ronnie Robinson, junior halfback James Betterson, sophomore defensive back Russ Conley, sophomore defensive tackle Rod Broadway and sophomore defensive back Early Jones, a walk-on from the baseball team.

Webster, now living in retirement in his hometown of Winston-Salem, peruses the list of the first 10 Black scholarship football players whose Tar Heel careers spanned 1968-76.

"Every one of us got our degree," he says. "The thing I am most proud of is we did not get caught up in football, did not get caught up in other things. We all graduated. I do not know of any other predominantly White institution who can say that about their early Black athletes."

Broadway, also retired and living in Myrtle Beach, reflects on how that first run of Black players formed a core of support for each other.

"If we had issues as young, Black, growing men, we didn't have anyone to go to but one another," Broadway says. "Charles Waddell was the person we leaned on, who we'd go to for advice. Charles learned from Web and Web learned from Ricky. Then by the time I left, we were getting more and more Black players. But for that first group, we had to lean on one another. That core group was very important to us."

Ricky Lanier died Oct. 1 at the age of 76. A number of Tar Heels paid their respects to Lanier on a Facebook page dedicated to Carolina football Lettermen. Among the comments were these:

"Thank you for being a trailblazer at UNC," wrote Eric Blount, a receiver from 1988-91.

"I really appreciate the privilege of riding on the road that you paved," said Cecil Gray, a defensive lineman from the late 1980s.

"He cleared the way for people like me, and I am forever grateful," added Chuckie Burnette, a quarterback from 1989-91.

Chapel Hill writer Lee Pace (Carolina '79) has been writing about Tar Heel football under the "Extra Points" banner since 1990 and reporting from the sidelines on radio broadcasts since 2004. Write him at leepace7@gmail.com and follow him @LeePaceTweet.

Jim Tatum knew of an outstanding football prospect in Shelby during his time as the Tar Heels' head coach from 1956-58. He alerted his friend Murray Warmath, the coach at the University of Minnesota, and told Warmath to offer Bobby Bell a scholarship. Warmath hemmed and hawed as he hadn't actually seen Bell with his own eyes, and there was no film of Bell available. "Look, if he doesn't work out, I'll pay for his scholarship," Tatum said.

Earle Edwards was similarly impressed with the prospects of a quarterback from Fayetteville named Jimmy Raye. Edwards, the N.C. State coach from 1954-70, called his friend Duffy Daugherty, the head coach at Michigan State, and put in a word for Raye, who was already on the Spartans' watch list because assistant coach Cal Stoll had been impressed with Raye's performance in a high school all-star game in Durham.

Ironically, Raye's first start for the Spartans was the season opener in 1966, when he led Michigan State to a win over the Wolfpack and Edwards.

"Would I have liked to have played at N.C. State or North Carolina, 60 miles from home instead of going 1,600 miles away?" Raye says today. "Of course I would. I would love to have played in my home state. But there weren't any opportunities. That's just the way it was back then."

Indeed, coaches like Tatum and Edwards were relegated to referring top Black prospects to their friends in the Midwest at a time before the color barriers had fallen at Southern institutions.

Bell played at old Cleveland High School in Shelby before integration and was a linebacker on the 1960 Minnesota team that won the national title (and no, Tatum did not have to reimburse Warmath for the scholarship). He also was a two-time first team All-America, in addition to winning the Outland Trophy and being recognized as the UPI Lineman of the Year in 1962. Warmath asked him if he knew any other good Black players from North Carolina. Bell said he had a good friend in Winston-Salem. That's how the Golden Gophers got Carl Eller.

Bell and Eller are both in the Pro Football Hall of Fame via their outstanding careers with the Chiefs and Vikings, respectively.

Gene Sigmon, a Tar Heel Letterman in 1962-63, mused about roster makeup from his era many years later. Sigmon was team captain in 1963, when the Tar Heels posted a 9-2 record, won the ACC title and powdered Air Force 35-0 in the Gator Bowl.

"You put Bobby Bell and Carl Eller on our team in the early sixties, and maybe we're talking about national championship instead of ACC championship," Sigmon said at the team's 50-year anniversary in 2013.

Fortunately, those inequities began changing just a few years later.

Dean Smith signed Charlie Scott as Carolina's first Black scholarship basketball player in 1966. Scott entered Chapel Hill in the fall of '66, played on the junior varsity basketball team and then had a record-setting and All-America career through his senior year in 1970.

Bill Dooley was hired as the Tar Heels' new football coach in December 1966, and one of his early recruiting targets was a dynamic quarterback and athlete from Williamston named Ricky Lanier.

Lanier was a standout on the 1966 E.J. Hayes High School team under Coach Herman Boone (of Remember the Titansfame) and was responsible for 13 touchdowns in one game—eight passing and five running in an 80-0 win over Snow Hill. Dooley wanted Lanier for the Tar Heels and arranged to have Scott and fellow basketball player Larry Brown serve as Lanier's hosts on his recruiting visit in early 1967.

"Larry and Charlie were just honest with me about what to expect," Lanier says. "I didn't think twice about being the first Black football player, but Larry and Charlie just did such a good job."

Lanier joined Dooley's first recruiting class that included a quarterback from North Wilkesboro named John Swofford and a tailback from Long Island named Don McCauley.

"He was a quality guy and on the outside was outgoing and happy-go-lucky," says Swofford, who lettered for three years and went on to a noted career in athletic administration, including 17 years as Carolina's athletic director and 24 as commissioner of the ACC. "You'd have to have walked in his shoes to know for sure, but any problems he had outside of football he seemed to handle very well. He was certainly accepted on our football team as just one of the guys."

McCauley echoes that sentiment.

"In our mind, there was no black/white," he says. "But Ricky was just another football player. It was an attitude of, 'Get to work and go play ball.' He was accepted for his personality and athletic ability."

Lanier displayed that athleticism at both quarterback and receiver while earning letters from 1968-70. He was moved to receiver but came back to quarterback for an early November game in 1969 against VMI because of a rash of injuries at the position. Lanier gained 218 yards running but lost 44 on quarterback sacks and a pitch-out that went awry to net 174 yards rushing for the game. That total remains a school record for rushing yards by a quarterback in a single game.

"Ricky made some outstanding runs," Dooley said. "We moved him to split end and then back to quarterback, and he gives us a good effort wherever we play him."

Swofford and McCauley wonder how Lanier's skills might have translated into modern college football with more passing and emphasis on getting elite athletes in space.

"In today's game with wide-open offenses and the way the ball is thrown so much, I think Ricky could be an extraordinary player—either as a receiver or a quarterback,"

Swofford says. "But that wasn't the kind of offense we ran at that time, very few teams did. Dooley's system was run-oriented with the option and pitch and not much throwing the football. It was a ball-control approach. It paid off ultimately as we won back-to-back ACC championships. Still, you wonder what he could have done today."

"Ricky was the first 'scrambling quarterback,'" McCauley says. "He had a great sense of where the defense was. He could really break down a defense."

After graduating from UNC in 1970, Lanier joined the coaching staff at North Carolina Central and later worked for IBM. He moved to Greensboro in 1990 and taught science at West Guilford High before retiring in 2016.

"I was never called names," Lanier said years later. "I think that the South and the nation just were in a transition when I came to Carolina. I never had any problems. The camaraderie with my teammates was great."

Lanier was the first domino to fall, and the color barrier officially fell for Carolina. One year after Lanier's arrival, linebacker James Webster and defensive end Judge Mattocks joined the squad. By 1974, the Tar Heel roster included six Black players out of 83—Charles Waddell as a senior co-captain along with senior defensive tackle Ronnie Robinson, junior halfback James Betterson, sophomore defensive back Russ Conley, sophomore defensive tackle Rod Broadway and sophomore defensive back Early Jones, a walk-on from the baseball team.

Webster, now living in retirement in his hometown of Winston-Salem, peruses the list of the first 10 Black scholarship football players whose Tar Heel careers spanned 1968-76.

"Every one of us got our degree," he says. "The thing I am most proud of is we did not get caught up in football, did not get caught up in other things. We all graduated. I do not know of any other predominantly White institution who can say that about their early Black athletes."

Broadway, also retired and living in Myrtle Beach, reflects on how that first run of Black players formed a core of support for each other.

"If we had issues as young, Black, growing men, we didn't have anyone to go to but one another," Broadway says. "Charles Waddell was the person we leaned on, who we'd go to for advice. Charles learned from Web and Web learned from Ricky. Then by the time I left, we were getting more and more Black players. But for that first group, we had to lean on one another. That core group was very important to us."

Ricky Lanier died Oct. 1 at the age of 76. A number of Tar Heels paid their respects to Lanier on a Facebook page dedicated to Carolina football Lettermen. Among the comments were these:

"Thank you for being a trailblazer at UNC," wrote Eric Blount, a receiver from 1988-91.

"I really appreciate the privilege of riding on the road that you paved," said Cecil Gray, a defensive lineman from the late 1980s.

"He cleared the way for people like me, and I am forever grateful," added Chuckie Burnette, a quarterback from 1989-91.

Chapel Hill writer Lee Pace (Carolina '79) has been writing about Tar Heel football under the "Extra Points" banner since 1990 and reporting from the sidelines on radio broadcasts since 2004. Write him at leepace7@gmail.com and follow him @LeePaceTweet.

UNC Men's Basketball: Tar Heels Battle Back to Top #14 Virginia, 85-80

Saturday, January 24

Carolina Insider - Interview with Reese Brantmeier (Full Segment) - January 23, 2026

Saturday, January 24

UNC Gymnastics: Tar Heels Down Pitt in Carmichael

Saturday, January 24

UNC Women's Basketball: Tar Heels Outlast Georgia Tech, 54-46

Friday, January 23